This piazza is the heart of Siena. This site revolutionised the idea of the medieval Italian piazza, having no spatial restrictions or conventional shape nor any symbolic balance of secular and religious power.

Piazza del Campo, view from the façade of the new Duomo

Conceived on a fragile and muddy piece of land, where the narrow streets of the old city converge, the piazza was a major urban planning problem for Siena.

The site was completely reclaimed during the Roman era, remaining, however, a suburban centre. The initial nucleus of the city was higher, in the Castelvecchio area. The future Campo was just a space for markets, off the main connecting roads that passed through the city. The first document mentioning the layout of the Campo was written in 1169 and refers to the entire valley including the current piazza and the Piazza del Mercato today is behind the Palazzo Comunale. At that time, the Sienese council bought the land stretching from the current Logge della Mercanzia to the current Piazza del Mercato - Market Place.

Giuseppe Zocchi, Night view of the Piazza del Campo with candlelight procession and parade for coming to Siena by the Grand Duke Francesco I, Duke of Lorraine and Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria on April 2 1739 (collection Banca Monte dei Paschi)

The first mention of a subdivision between the two piazzas was in 1193. From this we can deduce that a dividing wall had been built. On one side this gave the Campo its unique conch shell shape, on the other side the Mercato. Within the wall, small factories and workshops started springing up.

Until 1270, the site of the piazza was used for fairs and markets. The end of the aristocratic despotism of the Rule of the Twenty-four - il Ventiquattro allowed the development of a space independent of both ecclesiastic and aristocratic power.

This finally became the grand civic project ending with the construction of the Palazzo Pubblico and, consequently, the urban nucleus of the Campo. The Nove slowly got the project off the ground. The Palazzo was completed at the beginning of the fourteenth century and the Nove took up residence there in 1310. From then, the Piazza was progressively embellished and improved.

The surfacing of the piazza began in 1327 and finished in 1349. Even today, the centre is unchanged, subdivided into nine segments in commemoration of the Nove. The Campo, is a square shaped like a conch shell, surrounded by grand medieval buildings. Centuries later, these buildings have been deprived of some details, but their overall design remains. Indeed, apart from minor alterations to the buildings, the piazza as a whole has remained as it is for almost seven centuries. A project to crown the Piazza di Logge, designed by Baldassare Peruzzi, was shelved in the sixteenth century.

Sando di Pietro, Saint Bernardino preaching in Piazza del Campo

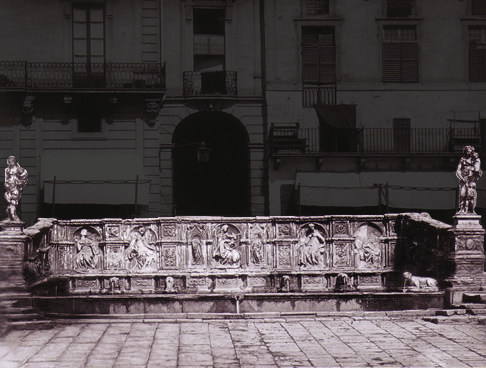

Fonte Gaia

Fonte Gaia, decoration by Tito Sarocchi

The fountain delivers water from outside the north of the city. The water passes along a ridge which doesn't meet any valleys or depressions along the way. To get the water to the fountain in the piazza it took Giacomo Vanni di Ugolino later called dell'Acqua eight years. He had to dig extensive underground canals called bottini.

Water arrived at the fountain in 1342 and was followed by a great Sienese celebratory party the reason the fountain is called gaia. It is the queen of the all Sienese fountains both because of its position in the Piazza del Campo, and because of its splendid design. The original fourteenth century fountain is known through its reputation and was replaced by the current design at the beginning of the fifteenth century. This was sculpted by Jacopo della Quercia sculpted between 1409 and 1419 and should be considered amongst one of the best examples of Italian fifteenth century sculpture.

Jacopo della Quercia, Fonte Gaia, Picture shoot before 1868

The fountain admired by tourists today is a copy by Tito Sarrocchi. The remains of the original, ruined by the ravages of time, can be seen at the Santa Maria della Scala museum.

Fonte Gaia, decoration by Tito Sarocchi

Water not used by the fountain still goes, via more or less functioning channels to supply the fountains of Pantaneto, San Maurizio, Casato and Pispini.

Other than the splendid fonte Gaia, which stands out in the piazza, moving along the Campo you can admire the beautiful Palazzo Petroni with its lovely three-mullioned windowed walls and Palazzo Piccolomini Salamoneschi to its side. On the corner called Curva

S. Martino, between via del Porrione and via Rinaldini, is Palazzo Ragnoni. Behind this are buildings later incorporated into the Palazzo Piccolomini. Further on we see Palazzo Mezolombardi-Rinaldini, now called Palazzo Chigi Zondadari. Going past vicolo dei Pollaioli, there are three gracious palazzi Tornainpuglia-Sansedoni, Vincenti and Piccolomini.

Palazzo Sansedoni

Fourteenth century in origin, these were significantly modified between 1760 and 1767, unified behind a single faηade in the style of gothic revival. Put together, however, with its compact brick and pink-red tones, the structure perfects the aesthetic of the Campo making an exciting contrast to the Palazzo Pubblico and the Torre.

The Palazzo della Mercanzia, also altered in the eighteenth century, lies between the

vicolo di S. Pietro and the vicolo S. Paolo. The two Saracini and Scotti palazzi, between S. Paolo and la Costarella dei Barbieri, offer a glimpse of the medieval design as it was originally, with only a few later modifications. This is also true for the Accarigi and Alessi palazzos/palazzo. These last two have conserved their beautiful guelphic merlons and the remains of their two and three mullioned windows. The last Palazzo is Mattasala Lambertini, with its stone base, right next to il Chiasso del Bargello and via del Casato di Sotto.

Il Palio

The Palio

The Piazza del Campo is also a theatre for one of the most time-honoured, sporting events, not just in Italy, but the world: Il Palio. The Palio is a competition that looks like an equestrian merry-go-round and its origins are medieval. The race - traditionally called the carriera - is held twice a year. On July the second they race the Palio di Provenzano - in honour of the venerated Madonna di Provenzano and the Visitation of the Virgin Mary - and on August the sixteenth the Palio dell'Assunta - in honour of the Madonna Assunta.

The Piazza del Campo crowded with Palio spectators

On exceptional occasions such as the first landing on the Moon by the Apollo 11 mission or on Sienese or national celebrations such as the centenary of the Unification of Italy, the Sienese may hold a special or straordinario Palio, between May and September. The last such was in 2000, to celebrate the new millennium.

According to certain sources, the Palio has origins as a memorial of the Battle of Montaperti (1260) and the narrow Sienese escape. However, the first accounts of the race are from 1333, and noting the layout of the Piazza del Campo, the race could only have started when its location was given its final and appropriate shape. It is said that for centuries the Palio and other horse races took place in a disorganised manner - of which only traces in certain documents survive.

Vincenzo Rustici, Bull hunting in the Piazza del Campo

The two main dates were fixed only relatively recently. The first, based on an old buffalo carriera organised by the Istrice, became the date of the Palio in 1656, when, for public safety, there was a ban on fireworks in the piazza to celebrate the Visitation. The second date became official in 1774, though the race had been held sporadically on that day since the first race organised by the Istrice in 1689. Both Palio races are now organised and managed by the Comune di Siena.

The Palio takes its name from the prize: Palio, from the Latin pallium a mantel or cloak - was also a type of banner made from a very fine, normally silk, fabric and was used for different purposes. In Siena, it was destined for the church of the winning rione

or contrada. It could be used to decorate the church or similar places. A fifteenth century pallium, decorated the altar of the Church of San Giuseppe, until recently.

From this came the church's popular name of Contrada Capitana dell'Onda The Capitan of the Waves Contrada. The Palio is a democratic competition, involving people from all the different contrade, giving it the kind of popularity aristocratic competitions could never afford.

Other than the already mentioned Istrice and Onda contrade, there are the Bruco, Nicchio, Leocorno, Lupa, Pantera, Selva, Tartuca, Torre, Valdimonte, Aquila, Oca, Chiocciola, Giraffa, Civetta and Drago. A total of seventeen contrade which representing every part of the city with their own supporters contradaioli.

Vincenzo Rustici, The parade of the Contrade in the Piazza del Campo in the sixteenth century

The contrade were assigned a specific territory, designated by boundaries in 1729 by the governess of Siena, Princess Violante Beatrice di Baviera. Due to incidents in previous years, she decreed that not more than ten contrade could race at any given time. This decision remains unchanged.

Every year the seven contrade excluded from the previous year's race the July and August carriere are considered independently are joined by three from amongst the previous year's participants. These three are chosen by lots. Each rione is assigned a horse, again chosen by lots from ten horses considered the most suitable. The assigning of the horses for the July Palio takes place on June the twenty-ninth and on August the thirteenth for the August Palio. This drawing of lots is known as the Tratta and is the first event in the four day calendar of festivities.

The carriera is preceded by six trial races, which take place on three mornings and three afternoons of the four day period. During these, each jockey, chosen by his contrade, is able to familiarise himself with his horse. The final evening trial race is called the Prova Generale the dress rehearsal - while the last trial race, run on the morning of the Palio itself, is called the Provaccia.

The Palio race itself consists of three laps around the Piazza del Campo, on a tufo - tuff stone - track dominating the shell-shaped piazza. The race starts from the Mossa, a starting point delineated by two ropes which form a pen. Inside the pen, only nine jockeys on the horses of their respective contrade get into their starting position according to the lots drawn. At the Costarella dei Barbieri there is a mechanism the verrocchio - activated by the controller of the Mossa, called the mossiere. He collapses the rope suddenly and the race starts at the precise moment the last of the ten riders - the one who remained outside - enters the pen. The winner is the contrada whose horse arrives first at the end of the three laps, with or without a jockey. These laps around the Campo create a unique spectacle: the arena of the piazza can hold up to forty thousand spectators on wooden platforms circling the track. On these the Capitano and the Tenente of each Contrada take their places.

In the past there were twenty-three contrade in Siena. Other than the current list, there is mention of six others, now called suppressed or dead contrade. These are the Gallo, Leone, Orso, Quercia, Spadaforte and Vipera. In the seventeenth century they were gradually extinguished. Their territories were incorporated into those of neighbouring contrade. There are traces of these in the crests of some the current contrade.